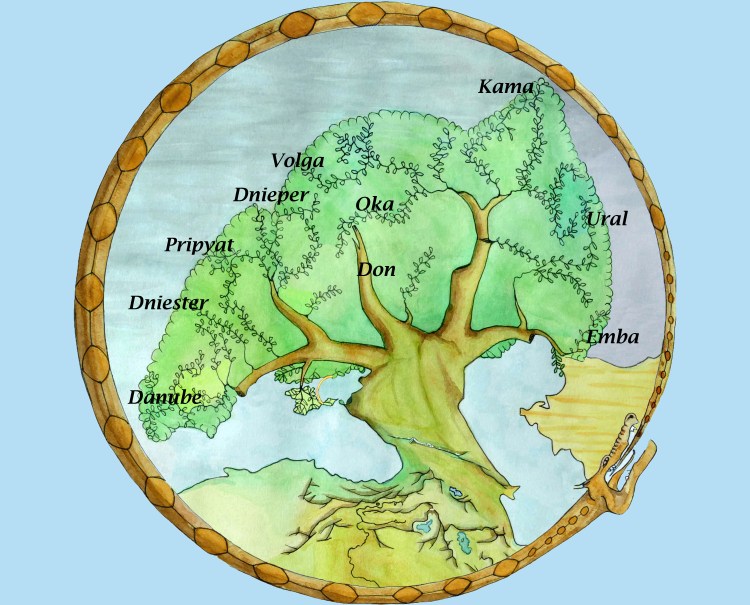

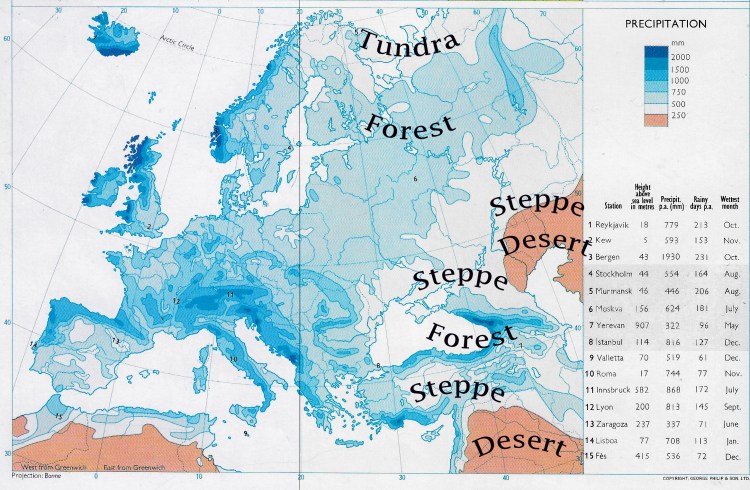

By the early Bronze Age the lakes and forests of the north continued to be the home to hunter-gatherers, the surrounding mountains were exploited for metals and fertile regions along rivers had long been farmed with large settlements established over time in some places.

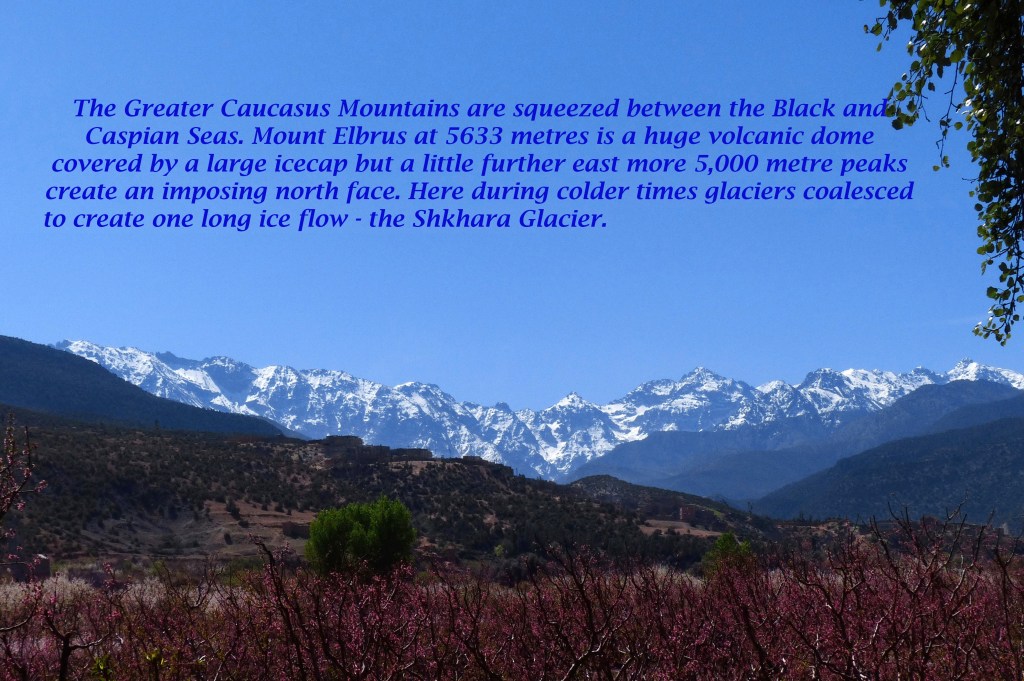

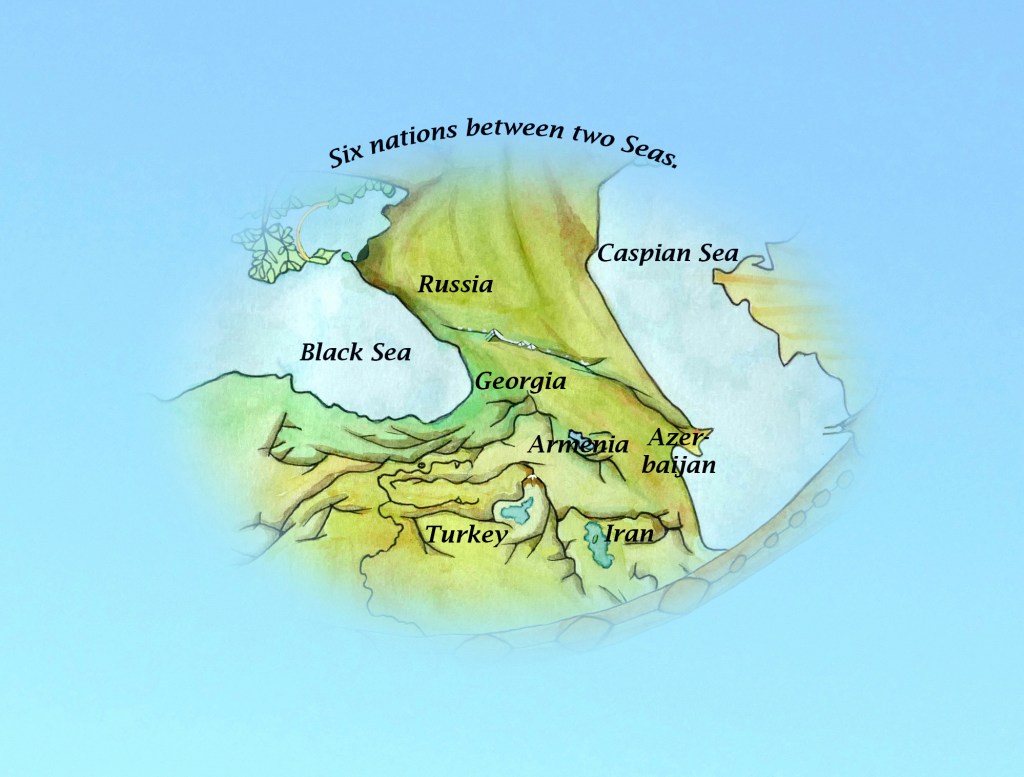

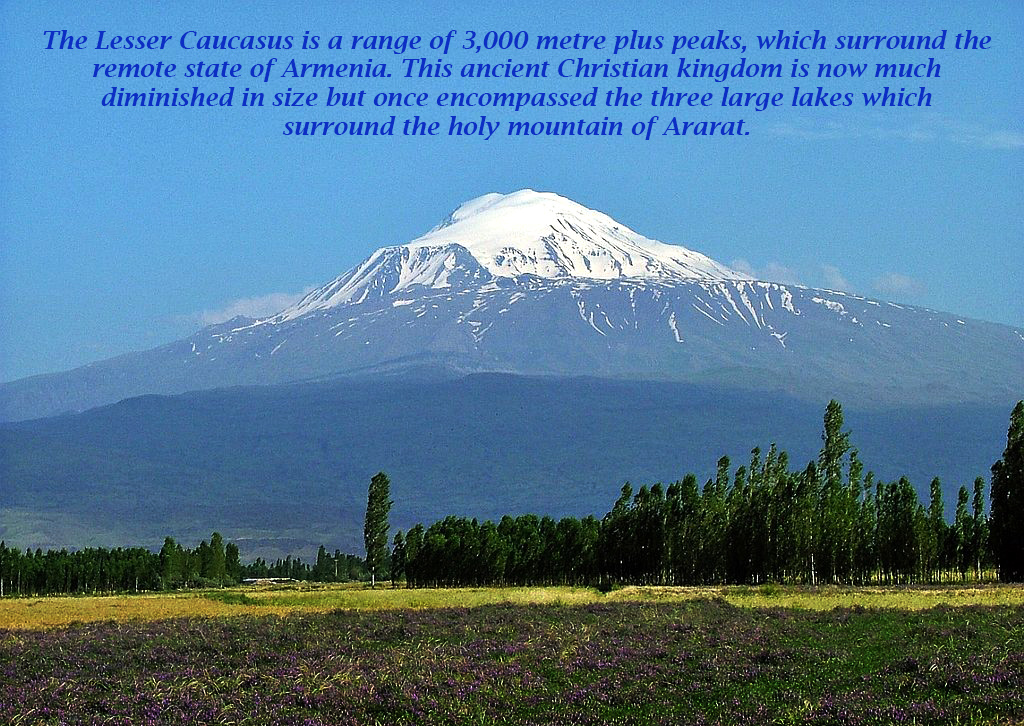

Sophisticated agriculture such as terracing and wine production were to be found on the flanks of the Caucasus, where advances in metallurgy were also taking place. Further south along the Euphrates River were emerging large urban centres while to the north on the wide grasslands a mobile steppe culture had developed around the invention of the wheel and the domestication of the horse.

Of these last people only their burial sites or kurgans have left any impression on the landscape or in the archaeological record but their impact on surrounding cultures stretching far beyond their homeland would be immense over subsequent centuries and even millennia spreading language and ideas across the whole world.

This culture, we refer to as the Yamnaya, then established itself around the shores of the Baltic during the Bronze Age and is sometimes referred to as the Battle Axe culture for these weapons were found in grave sites and judging from further archaeological evidence it was a weapon they were not afraid to use. This suggests that the take over by axe wielding, horse riding warriors of this and other areas was not done peacefully.

These sharp bronze axes had uses beyond weapons. They acted as an early form of currency and were adapted for cutting down trees. They also enabled the shaping of wood to be done more accurately and led to rapid improvements in boats and wheeled vehicles like carts and chariots. This in turn made societies more mobile and led to many more trees being felled for building but mainly to produce bronze needed in both smelting and mining of the ores. This caused an economic stimulus across the Old World and allowed the population to rise and more land given over to farming, which also benefited from bronze edged ploughs.