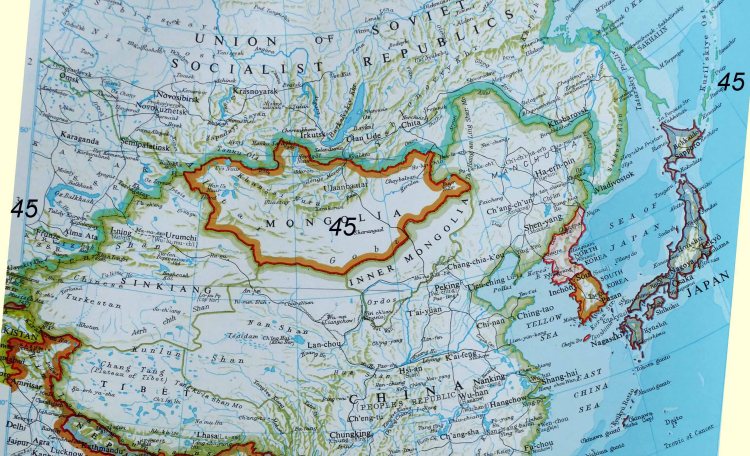

The 45th Parallel is a line equidistant between the equator and the pole that circles the world. In the southern hemisphere this crosses mostly ocean only passing over sparsely populated Patagonia and the southern tip of New Zealand known as Fjordland. The northern 45th parallel however crosses the widest part of both the Eurasian continent and the United States. It could be said to separate the cold north from the warm south, although because it crosses large areas of high ground this is not always the case.

Western Europe illustrates this quite neatly. The 45th parallel comes ashore in the famous wine region of the Medoc near the city of Bordeaux. The benign effect of the Gulf Stream just off shore gives this region an enviable climate of warm summers and mild winters. Yet just inland is the Massif Central where the climate average is closer to that of northern England. This difference is due to much of the region being over 1,000 metres. It has brief warm summers and cold snowy winters which is more typical for the latitude. A little further east on the French Italian border the line crosses the Alps. Just to the north of it is Mont Blanc at 4,810 metres with much of the top half of the mountain permanently covered in snow or glaciers. Receding slowly today just two hundred years ago glaciers threatened to destroy the now famous ski resort of Chamonix. Yet not far to the south is the sunny Cote D’Azur overlooking a balmy Mediterranean.

Back down near sea level the parallel crosses the northern plains of Italy, which again are hot and sunny in summer but can be plagued with freezing fog in winter. On the coast is Venice which throughout the Middle Ages was a strategic link as the Mediterranean’s most northerly port it traded between the hot dry Middle East and the lands of the north beyond the Alps. Continuing east the line follows the course of the River Sava and lower Danube to the Black Sea, which in classical times was seen for centuries as the border between the civilised Mediterranean cultures of Greece and Rome and the barbarous Germanic tribes of the north. The parallel then crosses the Black and Caspian Seas near their northern ends. Significantly north of this latitude the seas can be expected to freeze over in winter while further south they remain clear. Nowhere is this more apparent than the Crimea. This virtual island jutting out into the Black Sea has a balmy Mediterranean climate on its south side facing the sea and a rigorous steppe climate on its landward northern side. This southern ice limit is repeated where the parallel crosses the sea separating frigid Russia from the snowy island of Hokkaido and again off Newfoundland, where it crosses the notorious iceberg alley, made more dangerous by fog banks, close to where famously the Titanic came to grief.

East from the Caspian Sea is the fast diminishing Aral Sea. Here we find the most extreme weather yet. It is a desert which is searingly hot in the summer and bitingly cold in the winter when hit by an icy blast from Siberia not far to the north. Siberia is home to the world’s largest forest and to the south of the 45th parallel the land is mostly desert but roughly along it, stretching both east and west, is the narrow band of grass steppe. Further east the terrain becomes mountainous with the Ili Valley just to the south of the parallel, the last fertile region for some distance, and to the north are the remote and desolate Dzungarian Gates on the border of Russia and China.

The parallel then continues over the bare windswept mountains of Mongolia constantly overlooking the border of China someway to the south. These mountains are the source of a number of rivers whose waters flow north across the vastness of Siberia while to the south the mountains merge into the Gobi Desert stretching east along the parallel and is also a boundary between the fertile and populous plains of China liying just behind its Great Wall and empty arid Mongolia. Further east though the Manchurian part of China does cross north of the 45th parallel at Harbin but in winter this is known as the freezer of China much as Minnesota standing on the same latitude in the American midwest is known as the freezer of the U.S.

Where the 45th parallel crosses the Pacific it leaves Asia by passing over the stark volcanic Kuril Islands plagued by drift ice in the winter and fogs in summer but where the parallel makes landfall across the ocean in America the moist and mild influence of warm ocean currents create good growing conditions in the favoured and fertile Willamette Valley protected by a coastal mountain range from the full force of winter storms. After crossing the valley the parallel keeps close to the mighty Columbia River before crossing over the Rocky Mountains to follow the long southern border of Montana, whose climate has more in common with Canada than the U.S. but with all these places that suffer severe winters they also have hot if sometimes brief summers. Snow is the other factor of cold in the mountains of Wyoming just south of Montana, Maine which straddles the 45th parallel in the eastern U.S. and just to the south of this line of latitude around Buffalo all are famous for prodigious amounts of snow. The mighty Niagara Falls just north of Buffalo can also spectacularly freeze over as will the Great Lakes during a hard winter with the 45th parallel crossing Lakes Michigan and Huron.

Finally the parallel crosses the Atlantic to close the circle on returning to France but here is found the biggest anomaly of all. The line first passes through Halifax, which has the distinction of being the only major year round ice free port on Canada’s eastern seaboard. On the other side of the Atlantic however the North Atlantic Drift, which is the northern extension of the Gulf Stream, keeps the European coast ice free throughout the year well to the north and east of Norway’s North Cape at a latitude of 70 degrees. For early explorers going as far back as the Vikings this must have been very confusing but to no one more than the famous English explorer Henry Hudson on his final and fateful voyage in the early 17th century.

Having already explored the high arctic beyond Norway and rediscovered Spitsbergen (Svalbard) he was commissioned to search for the Northwest Passage. He was successful in discovering the entrance to Hudson Bay and sailed south in search of an exit not knowing that it was an enclosed bay. Unfortunately winter was closing in, but by the time he had reached James Bay at its extreme southern end he had reached the same latitude as London and must have thought that winter should not be too severe there. He could not have been more wrong, his ship was locked in ice until June and on being released his crew mutinied and cast their captain, his son and a few other officers adrift never to be seen again. He was only the first of many explorers to underestimate the extreme cold of the Canadian Arctic with the tundra stretching as far south as the 55th parallel and the possibility of spotting a polar bear this far south when the sea freezes for half the year. Yet the anomaly does not lie so much with Canada but more with the Gulf Stream keeping the western fringes of Europe unusually warm for their latitude. As described below this influence can fluctuate over periods of time, with Europe having passed through regular cold phases in the past.

A post Ice Age climatic optimum several thousand years ago encouraged tribes, whose numbers had swelled in the fertile valleys of the southern Caucasus, to cross over the mountains and move north along the fertile land corridor between the Black and Caspian Seas. Steadily pressing on further north they discovered wide fertile grass plains stretching far to both east and west. They had ventured well beyond the 45th parallel but they would have been blissfully unaware of this, though they quickly found winters to be much colder than they had been used to. They needed to adapt or ultimately perish, but this they did showing a huge amount of flexibility and ingenuity to become some of the most inventive and successful tribes of this formative period in human history, which would set the stage for a modern world that we recognise. They had one great handicap which was the lack of raw materials like metals but these were available in the surrounding mountains which they acquired by either raiding or trading.

They were renowned for their mobility thanks to being the first to domesticate the horse and later this was enhanced with the invention of the wheel allowing for the first horse drawn vehicles soon to be followed by the development of the chariot. With these advantages they were able to spread far and wide; even beyond the steppes and into quite different habitats. Some returned south over the mountains and were able to take over lands richer and more populous than their own. Some others moved further north following long fertile river valleys which stretched deep into the forested hills of the interior. Here they learnt of other rivers flowing into a large inland sea to the west where there was talk of lush pastures. These folk were principally cattle herders relying on meat and milk, the latter of which they had learnt to turn into other longer lasting products like butter and cheese which they had evolved to tolerate.

Like their southern counterparts along with their mobile lifestyle they had also adopted a mobile form of warfare with fast surprise attacks on horseback for which their opponents had little answer. They were thus able to sweep across the land taking control over large areas of the North European Plains all the way to the Atlantic. Many settled around the Baltic Sea and its many rivers opening up the area to cattle. The winters were no colder than on the steppes and they had greater means to avoid the wind with the shelter of trees and timber to build sturdy shelters and provide fuel. It was mainly the summers that were different for sometimes they could be cloudy and wet. Here there was also the opportunity to trap or hunt for furs and there were plenty of fish in the sea and rivers but their biggest bonus they discovered was precious amber with which they could trade for necessities like metals.

Again they had adapted successfully to their circumstances and during the Bronze Age they flourished but steadily the climate worsened with the drab wet summers beginning to predominate and occasionally having to suffer the harshest of winters which would freeze over the sea and dragged on into Spring so that the sea and rivers might not thaw until after the swallows arrived.

The 55th parallel which passes close to the border of Denmark and Germany and then close to the southern Baltic coast is significant in that north of this latitude for two months of the year or 60 days of mid winter the days are less than eight hours long or looking at it another way the nights are twice as long as the days. At this time of year the sun rises in the southeast and sets in the southwest with a trajectory of just 35 degrees above the horizon, it hangs very low in the sky all day. This trajectory remains the same in mid summer but with 16 hours above the horizon and rising in the northeast and setting in the northwest it has plenty of time to climb high into the sky. During the summer solstice the sun is only about ten degrees below the horizon at midnight and looking north across the Baltic the sky does not turn fully black with a faint blue glow persisting along the horizon. It is no wonder that all these facts and co-ordinates were a fundamental part of their religious beliefs and from earliest times they and the luna cycle had been calculated precisely.

All this means is that as with the 45th parallel where seasonal temperature extremes are a feature then on the 55th parallel the main feature is sunlight or lack of it. In both cases but more so with the more northern parallel the amount of cloud cover has a dramatic effect on temperatures so that a sunny summer will be warm and ripen crops quickly while clear skies persisting through winter will allow temperatures to plummet. In winter Atantic storms penetrating far inland would bring heavy snow falls but in summer persistent cloud and rain would not allow crops to ripen.

This scenario is close to the climate of Scotland where maritime influences predominate giving the country mild wet winters and cool dull summers, which is in contrast to Latvia which lies on a similar latitude but more exposed to continental influences giving warmer summers but much colder winters. All lands in between are gradations of these two extremes but the climate has always oscillated so that sometimes maritime weather predominates and at other times continental weather takes over. At the moment the climate is in a maritime phase fueled by a strong jet stream especially in winter pumping mild air even into the Baltic. This can easily change as during the Little Ice Age, which lasted through several centuries up to the mid 19th century. Then there were many exceptionally cold winters when even in England frost fairs were held on a frozen Thames in London. The coldest years could reduce the growing season by a month in northern latitudes down from six months to five. This 17% reduction in productivity would not only impact on yields but create the need for extra provisions to last the winter and the gathering of extra fodder to keep livestock fed during this time. Without outside help this would push whole tribes living in marginal areas over the brink forcing them to move south thus putting pressure on other tribes.

There were also cold periods either side of the height of the Roman Empire, a period lasting around 400 years when the climate remained generally benign. Without the conveniences and science of the modern world folk back then had to adapt as best they could but extreme weather events would also in time alter their world view, especially in the more northern latitudes. They found themselves struggling to live in what had become a forbidding environment of stormy skies, dark forests and icy waters. Warm south westerlies had been replaced by bitter north easterlies and furs were becoming harder to procure. They spent long winters huddled around fires passing the long dark hours telling stories and trying to explain to the younger members of the tribe how things came to be so. At the same time on the eastern steppes there were episodes of drought which forced the tribes there to move west in search of greener pastures causing those on the western or Pontic steppes to also drift west putting pressure on the forest tribes. This added pressure was enough for these tribes to push south and even break through into the Roman Empire at a time when its might was already waning.

The situation reached a low point around the mid sixth century when the weather turned exceptionally cold for a number of years with outbreaks of the plague in southern cities travel was difficult and dangerous causing long established trade routes to collapse. For several years northern tribes found themselves isolated in a climate not fit for man or beast. The weather did slowly improve with occasionally good autumn harvests returning, less severe winters to endure, more promising springs to lift the spirits and brief bright summers in which to recover, though overall it remained changeable and unpredictable. In such trying circumstances hope hung on little things. It taught folk to make the most of any positive sign to help keep them going through the dull days and cold nights.

In higher latitudes it was very much the case that weather could lurch to extremes of both good and bad. When it was good it was beautiful, the greens were fresh and the flowers vivid in Spring and summer days could still be balmy lingering long into evening. Autumn would put on a fantastic display of colour and even clear still winter days were invigorating. Nothing was taken for granted and nature and the weather was watched closely for signs that might predict changes, which was the only constant. When the first cold blast might arrive, when the ice might finally thaw, will the cold winds ease and will the weather hold long enough to bring in a successful harvest. They watched the comings and goings of the mass flocks of migrant birds, the rise and fall of rivers, the first and last frosts, the behaviour of insects and other creatures and the moods of an ever changing sky.

Weather patterns only began to be understood in the second half of the nineteenth century with the introduction of the telegraph which allowed weather information to be reported instantly from distant and even remote places. This enabled a picture to form of how big a storm was and which way it was moving. Before this no one knew if a storm they were experiencing was a local phenomenon or whether it stretched across the country. It took another century for forecasts to confidently predict weather more than a day ahead thanks to an array of satellites having been put into space during the last quarter of the twentieth century to watch storms develop far out to sea. Today powerful computers can even predict general weather patterns before they have even formed.

All our ancestors could do however is construct a whole folklore around natural phenomena and this in time became the basis of a uniquely northern religion with roots and a purpose quite different from those that evolved by people to the south of the 45th parallel in the fertile oases and rich cities. They looked north and judged its inhabitants as barbarous and called them heathen forgetting that some of them had originally come from there and that many innovations and inventions took place there. This was dangerous and in time they would suffer from underestimating their tenacity and adaptability. This inventiveness was based on their close link to nature and showed first in their artistry but would ultimately lead to much more like sleek ship design and advanced weapon making. Again as in the early Bronze Age they had developed a type of raiding warfare that their opponents had no answer to but this time it was sea borne rather than on horseback but the parallels are clear to see.

Their first priority after the extreme events of the mid sixth century though was to re-establish trade routes. In reverse to their early Bronze Age migration routes of the Bronze Age they ventured south down the long rivers of the interior to emerge by the Black and Caspian seas from where they could easily access the great cities of the south. Sometimes this meant fighting their way through hostile lands causing a reputation to spread before them of being marauders. This would make it more difficult to negotiate safe passage and trade deals, which was also the case when they ventured west by sea in their sleek versatile ships that could cross oceans or as easily sail far up rivers shocking the local inhabitants when they appeared without warning.

Another handicap is that during their isolation the world that surrounded them had become fiercely and uncompromisingly Christian, and having had to deal with Muslim incursions as far north as the 45th parallel, this made them immediately hostile to what they perceived as a pagan threat. The heathens meanwhile found undefended and exposed monasteries easy pickings with interiors encrusted in precious objects which had no relevance to them other than as bullion. Rather than mindless heathen marauders they were motivated by loyalty and honour to improve standards for their loved ones back home who had been barely subsisting for decades.

Even now when we look back peering deep into the past we have difficulty understanding their motivations often judging them as ignorant folk stumbling through a great tract of northern wildwood. Our view was prejudiced early on by how the Romans and other literate societies regarded their non literate and non urban counterparts. Yet buried in books or listening to biased sermons one can become divorced from the natural world and what it can teach you. The real truth is that you never stop learning and discovering new things once you are immersed in an environment rich in diversity. All you have to do is look – up, down, under, over, near and far but most of all early and late. Those locked into a 9 to 5 world are only living half lives failing to see the vast range of beauty the natural world has to offer.

Living close to the 45th parallel is generally the best place to witness the steady change of the seasons which seem to go at just the right pace to enjoy them fully, especially if you are an outdoors type of person. For each season there is something to look forward to. This can be a refreshing outdoor swim on a hot summer’s day, a misty autumn day spent foraging in tinted woods and along laden hedgerows for mushrooms and berries, in winter a brisk long walk crunching through frosted snow and long shadows and best of all when spring arrives witnessing the return of a warm sun encouraging the land to burst into bloom with the most vivid and vibrant colours of the year. These are experiences our ancestors could also have enjoyed but in quite a different context. Where we might quickly move on to another type of experience for our ancestors this would be as good as it got and would be absorbed and cherished the more so for it. Perhaps more than anything we are guilty of not lingering and should remain in the moment instead of always planning ahead.

To experience the best nature has to offer it is necessary to be up before the sun and linger outside until after it has set. In northern latitudes this is easy in winter but takes commitment during the long summer days but is most rewarding in spring and autumn. These are times of the year when not only the countryside is changing day by day but the weather is changeable too. It can easily jump back and forth between winter and summer each time the wind changes from a gentle breeze wafting up from southern climes to switching suddenly to a chill northern blast. One of the greatest boons of modern technology is having devices to tell us what the weather is going to be several days hence and with the same device locating somewhere nearby where conditions are best favoured for appreciating the latest spectacle that nature has to offer.

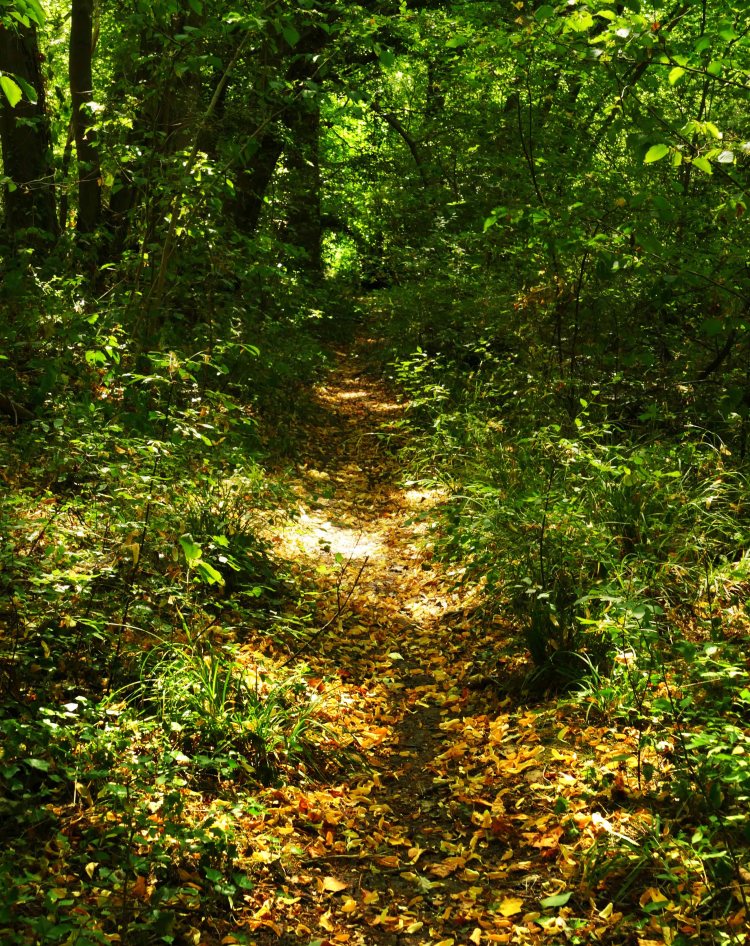

The major challenge is that in the mobile and informed world of the 21st century unspoilt natural places can be hard to find and the obvious ones can be busy. This is another reason for going out early or late and not looking for the obvious but seeking out the subtle. If you are fortunate certain conditions might occur that connects you briefly with a time when nature still held sway over man. Even though I live in an area where the land is intensively farmed there are still places that have yet to come under the plough and if lucky with views where there are no obvious modern intrusions to spoil the mood and break the spell of stepping back into an unspoilt world. The sequence of photos that go with this post are nearly all taken in the same area, between latitudes 53 and 53.30 degrees north, where farming is an industry which demands large vehicles working huge fields in a constant cycle of production to feed a constantly growing population. Only precious pockets of unspoilt or protected land remain such as old pasture, ancient woods, untamed rivers and wild coast. Occasionally man can still be in harmony with nature as in the case of areas of woodland pasture or old byways where thick hedges can grow. Given a chance nature will seize opportunities to flourish as along wide grass verges or abandoned quarries or gravel pits. All untended places are worth exploring because nothing is more opportunist than nature.

A good indicator of finding somewhere unspoilt is sound. There should be plenty of natural sounds like bird song, rustling leaves and running water. Cattle lowing and the bleating of sheep are acceptable but the noise of traffic even if it is a distant background hum is not. Today this noise is so omnipresent that we unconsciously block it out. When crossing a busy road with cars passing at the national speed limit you then understand why the sound travels so far and why it is so frightening and disorientating for wildlife.

Today a recognised indicator for the health of the countryside is by counting species or the size of flocks but in the past this would have been regarded as absurd. The size of flocks back then could be so large that they would be impossible to count unless it was to the nearest hundred or even thousand. While the sky back then might have darkened due to clouds of birds passing overhead there were also times when waters would erupt with life and boil with activity. During salmon runs rivers would seem to be alive with fish and herring shoals just off the coast would be in their millions. Both would attract large predators with bears and eagles along the rivers and large marine mammals and tuna attacking the herring with humans also struggling to get their share while being dive bombed by gannets. The course of rivers would be determined by beaver dams rather than human ones. The former encouraging diversity and the latter blocking it.

Now domesticated animals dominate the world all of which are counted in billions. This includes both animals to eat and pets to entertain us. For every human on the planet there needs to be a field full of animals to sustain him. This is why space of any kind is at a premium and in a human dominated world wild space is diminishing fast. Even the skies are crowded with jets. So finding places without vapour trails overhead is the most difficult of all.

With all these considerations it is best to find a deep wooded valley with a clear stream flowing through where you can hear only small sounds and concentrate on the mosaic of details that surround you or by contrast a remote exposed stretch of coast where the elements are still in charge with the roar of the sea and purgative effect of the wind and the liberating sense of wide open horizons can recalibrate your view on life. Don’t however wait for a nice warm afternoon to do this but go on moody days such as cool stimulating misty mornings, afternoons that threaten a storm and a post storm evening when the rain has cleaned the air promising a coal black star filled night sky.

You often can tell when you have found a good place because there are no straight lines to be seen. This includes no forest rides which allow vehicle access. In the original wildwood even paths would not be straight because of the barriers formed by fallen ancient trees, boggy ground and tangles of thorns. All these things seem problematic to the modern mind but to wildlife they are essential cover where they can carry on their lives largely unseen.

We as intruders have a duty to pass through largely undetected leaving little or no evidence of our presence. Moving silently we might be gifted with glimpses of the wild, which our ancestors were so familiar with but it is still distant in many ways from their experience. Not only would they see more but more importantly they were able to read more about what they saw. Theirs was a multi sensual three dimensional reading of their surroundings much more compelling than any immersive computer game yet to be devised.

At the mid latitude of the 45th parallel the trees, except for in the mountains, are mainly deciduous, an adaptation that evolved specifically to cope with seasonal extremes. They shed their leaves in autumn to remain dormant through the long winter. North of this latitude at this time wildlife has to decide how best to cope. Many birds migrate to warmer climes, some mammals from bears to bats fatten up to slumber through the coldest months, while insects seem to totally disappear only to reappear miraculously in spring. We are able to turn up the heating and carry on but this has only recently been the case.

If you lived on or above the 45th parallel a thousand years ago and had a disappointing harvest then your main concern would be – was there enough food to last the winter? Keeping warm would be a constant chore having had to create a huge log pile even before winter started. Lighting would come mainly from a central fire with maybe a few flickering candles to aid specific jobs like needlework. Trips outside would be regular with plenty of pee holes in the snow surrounding the dwelling. All the while at the back of your mind would be the thought that if elsewhere conditions were worse come Spring would these people in desperation raid your meagre rations or remaining livestock. Spring would bring relief but also hard work to a weakened body. Only after harvest would there be a brief respite before preparation for winter would start again and the further north you lived the smaller this window would be.

While today we have the advantage of checking the weather before planning activities whether for work or play and adjust them accordingly depending on the forecast, maybe grumbling if a little if rain was on the way, our forebears would be watching every sign available to them looking for patterns to the seasons. This weather lore would not only involve watching the skies but also for any other clues that nature might offer. In Spring this might include when toads start their mass spawning, the steady return of migratory birds and the flowering or leafing of trees, shrubs or flowers. This would be a concern right through the year keeping a close eye on the changing seasons in anticipation of different events and challenges. It was an all consuming and integral part of life with folklore evolving and the telling of stories of extreme years and any portents there might have signalled the possibility of a hard winter, wet spring, summer drought or stormy autumn. During turbulent times of extreme weather they would also call on their gods to intervene and spare them from such hardship.

Even today with regards to insurance policies we still refer to “an act of God” which shows how recently we believed that such things as weather were due to divine intervention. Yet most modern religions put man at the centre of all things. This human centric view evolved in urban settings and with religions remaining very centralised, dogmatic and hierarchical they changed little over time. The intolerance of some Christian societies was clear to see at the beginning of the Age of Exploration when it was first realised that heathens across the world outnumbered Christians with a reaction among the ruling elite that this statistic should be reversed by whatever means necessary, which in some cases would have shocked a hardened Viking warrior.

The Spanish conquest of the Americas had parallels with the Viking attacks on western Europe. The first phase was looting the religious treasures of the Aztecs and Incas and melting down works of art into bullion followed by settling large areas that were good for European type agriculture and using slaves to increase their productivity and profits. When Europeans suddenly appeared in the Indian Ocean at the end of the 15th century, which had been an almost exclusively Muslim sea for centuries allowing them to control the spice trade, it must have been similar to the first Viking raids at the end of the eighth century in Europe. With the parallel that in both cases during the next two centuries these isolated attacks escalated into wholesale invasions.

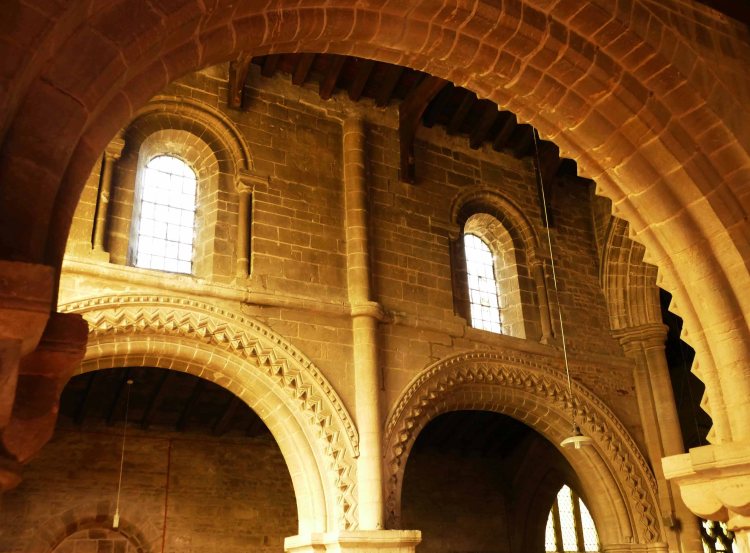

The Reformation in the 16th century followed by the religious wars across the northern half of Europe in the 17th century were based on a rejection of the centralised and dictatorial form of Christianity that had held sway over Europe during the Middle Ages. In the early part of this period this hierarchical system conveniently tied in with the formation of nation states under a single ruler but as feudalism loosened its grip on Europe with the growth of towns and cities run by an emergent and literate middle class this orthodoxy was inevitably going to be challenged.

The old catholic orthodoxy had least relevance in the northern half of Europe and had been embedded there for the shortest amount of time. It had taken many centuries from the end of the Roman Empire to slowly convert these northern lands to Christianity. To begin with there were successes thanks to the preachings of at first Irish then followed by Anglo-Saxon itinerant monks, but the bullying tactics employed by Charlemagne set back this conversion by a couple of centuries. It was not until the 12th century that remote parts of Europe around the eastern Baltic were finally converted. It is not surprising then that Scandinavia and northern Germany not only were the first to embrace Protestantism but today have also embraced the new environmental revolution. Maybe this has to do with a faint lingering resonance of the old natural folk beliefs that had been prevalent in the north.

Animist and folklore beliefs have always been more localised, rural and flexible and believe in a much closer association between man and the natural world. Today science is finally beginning to reveal that we are not only closely linked with nature but that our recent actions are responsible for upsetting its balance. This will not only impact on nature but our own well being. It is clearly time to reverse the mistakes we have already made and revere nature once more by creating large sanctuaries of wildwood and untamed heathland for key species. Rewilding and the reintroduction of apex predators to return a balance to nature, as has already happened in Yellowstone N.P. should also be on the agenda. If we are not ambitious about helping nature to help us then not too far in the future when the impact we have inflicted on the planet becomes irreversible we might find ourselves back on our knees and praying for deliverance.